The Art of Motion: Olga Szentpál by Boglárka Heim and Eszter Petrány

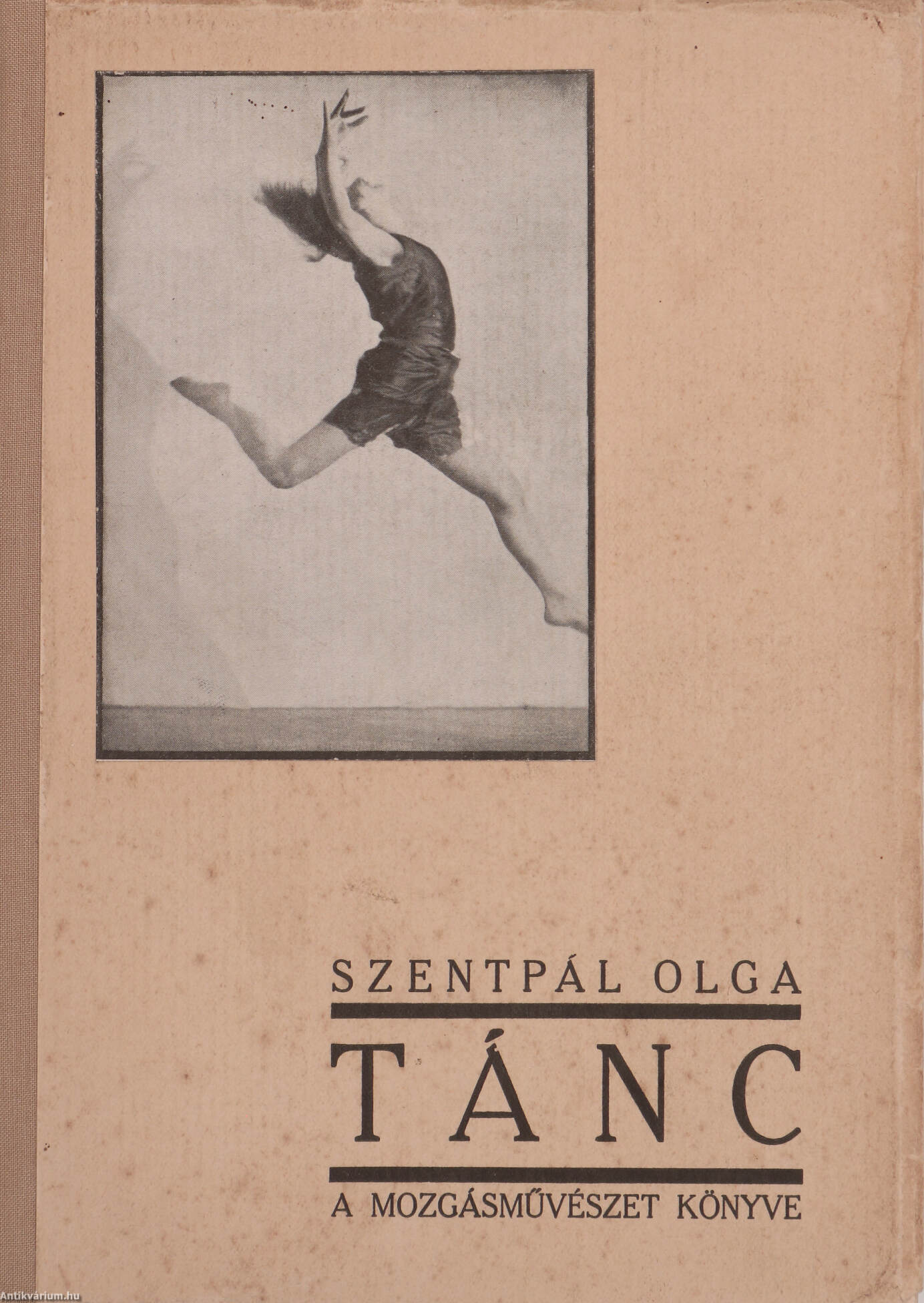

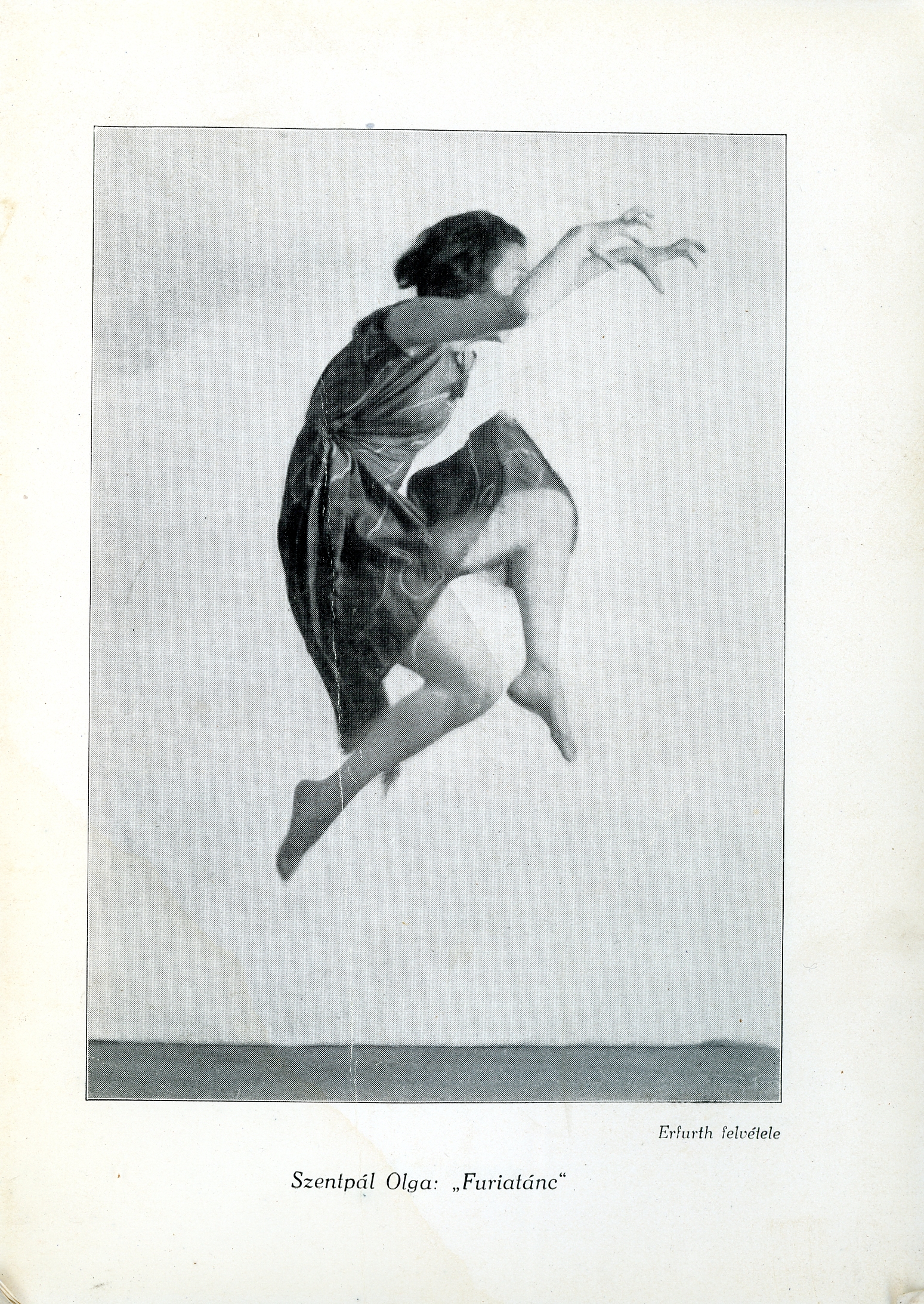

In 1928, Olga Szentpál (Budapest 1895-1968) published the book Tánc – A mozgásművészet könyve (Dance – The Book of Art in Motion) together with Mariús Rabinovszky, in which she described a systematisation of dance movements and movement compositions. The book is illustrated with reproductions of works by the German photographer Hugo Erfuth and the Hungarian Olga Máté. This book has not yet been translated into English or German.

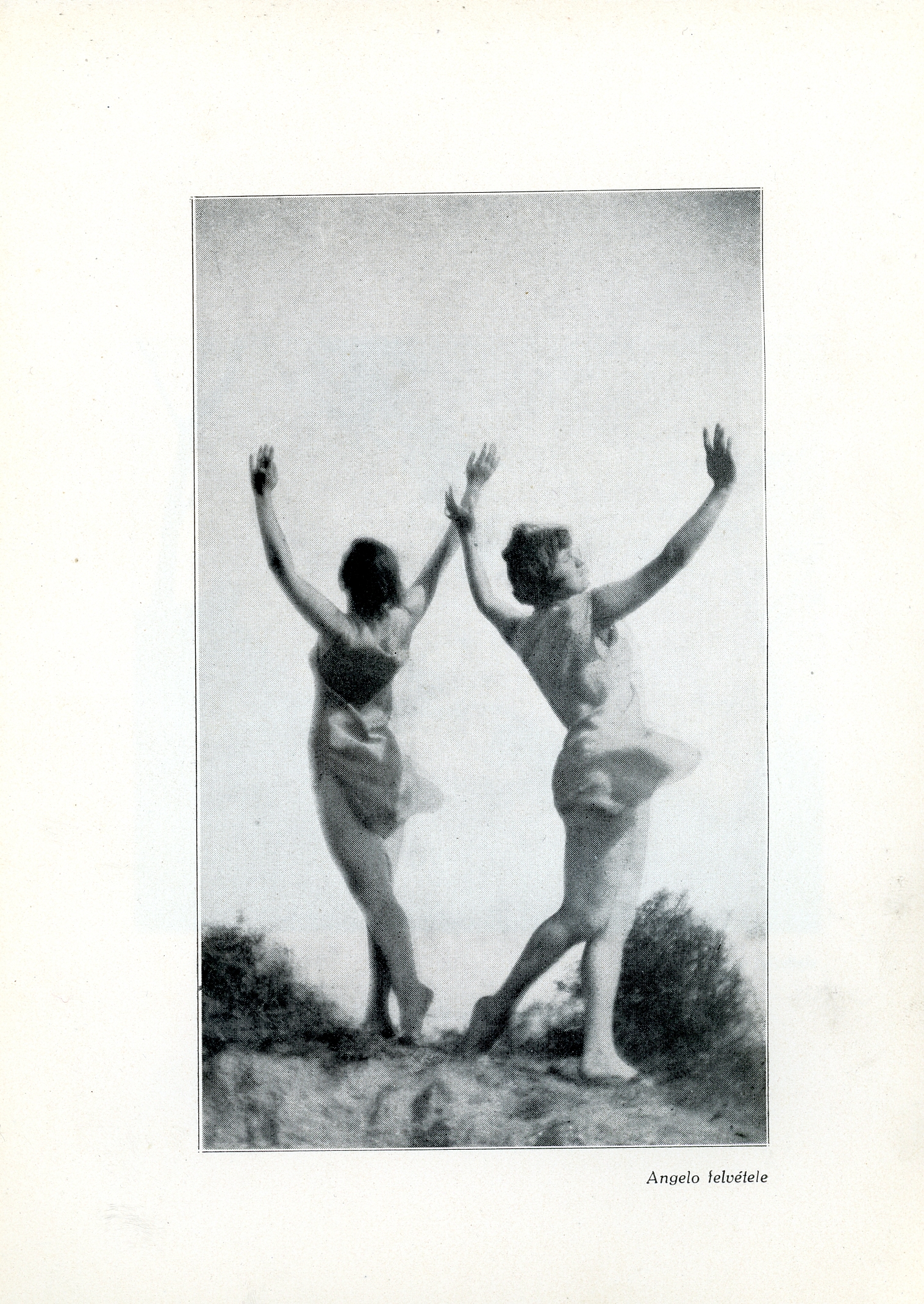

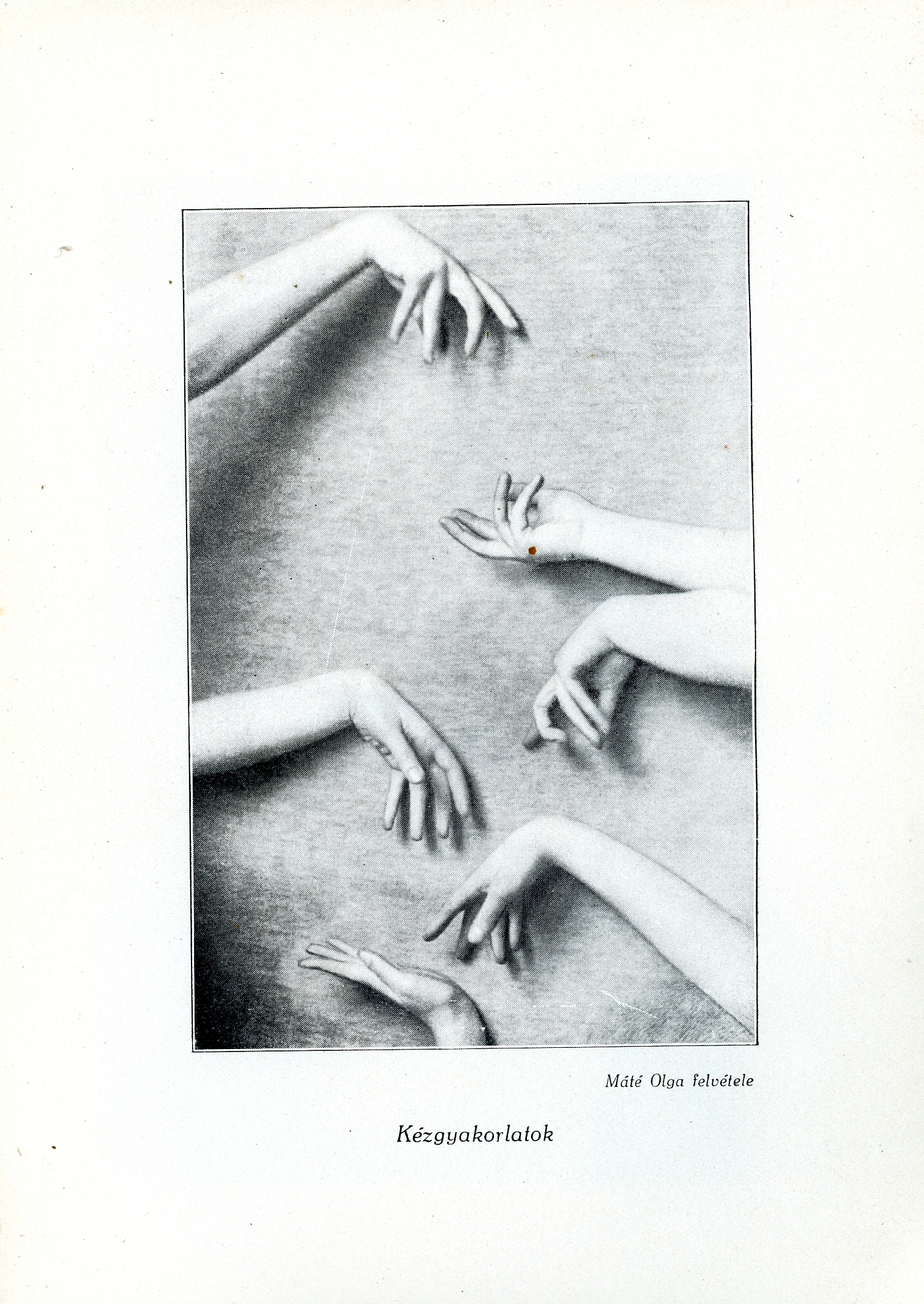

Eszter Petrány and Boglarka Heim extracted passages from these writings and worked with the specific dance terminology that Olga Szentpál was using. The photos became a main reference points for them to re-create Szentpál’s ideas about expressivity, movements and performance. The Notations of Maria Szentpál (1919 – 1995, daughter of Olga Szentpál) on Hungarian Dances became another source of reference for their artistic research. In combining Szentpál’s movement principles (e.g. specific rotations of the body, different types of touches and holds, articulations of the feet, partial and complete weight shifts) Eszter and Boglárka experimented with new bodily and artistic solutions in their dancing.

(Text: Rose Breuss)

The Art of Motion

dancers: Eszter Petrány, Boglárka Heim

research inspired by Rose Breuss

cinematographer: Natália Meister

editor: Marcell Török

Review of the book that served as the base of our research

Olga Szentpál és Dr. Márius Rabinovszky: Tánc – A mozgásművészet könyve (1928)

This joint volume by Olga Szentpál and Márius Rabinovszky was born as a record of the pedagogical work of the Szentpál School, mainly recording observations, discoveries and results during the period between 1916 and 1928. In fact, the book serves as a guide to dance pedagogy and performance art, which is unique because until its publication, the methodology of the art of movement had not been discussed in its entirety and in its context neither in Hungarian nor in foreign languages. Drawing on practical experience, it organises theoretical insights in a way that is as transparent and usable as possible for dance teachers and artists of the time. A special feature is that the methodological descriptions – which are almost rigidly structured – are followed by an illustration of nearly thirty pages of dance photographs taken by Hugo Erfurth, Olga Máté and Angelo. These photos partly show gestures, movements, spatial forms and poses taken from Olga Szentpál’s choreographies, and partly recall exercises and practice sequences from the school’s curriculum. In this case, the illustrations are not presented as appendices to the volume, but as information on a par with the methodological written part, showing a great deal of the elements, tools and the whole spirit that seeped through modern dance to Olga Szentpál, her students and colleagues.

Szentpál divided the classification into two main groups. First, she examined and analysed dance from an artistic point of view, then she focused on methodology, technical analyses, rules and terms. In the first part, which unfolded artistic perspectives, she laid down basic principles such as the fact that movement art always means artistic dance. She distinguishes between sport, movement without purpose, game-like dance and dance art.

Human life takes place in an intricate richness of the different senses. Human movement loses its primordial primitiveness and uniformity and adapts to the demands of practical life. It is so complex: from the panther’s squeak, leap, and pace through the finger that runs over the testers of the typewriter, the foot leaping on the moving tram, to the complicated expediency of the hand driving the steering wheel of the car! But human culture has also developed movement in other directions; a gesture of the hand, a twitch of the facial muscle, can sometimes reveal the wonderful depths of feeling, can sometimes express hidden experiences of the soul that words could never express. Human movement develops in two directions: towards expediency and towards expressiveness.

(Szentpál, p.14)

The first part of the essay begins with a moral programme, placing dance in the palette of the arts and then giving it a value in keeping with the ethos of the time. The moral programme makes it clear that the Szentpál School did not want a new dance, but an artistic one, and that modernity was not a conscious aim, but an arbitrary consequence. It contrasts modern dance trends, the so-called reform movements, with classical ballet, while at the same time formulating a strong ‚oppositional‘ critique of the ballet seen in Hungary at the beginning of the 20th century. This is followed by a definition of the art of movement, and then by other issues examined from an artistic perspective, which provide the reader with quite new perspectives (and thus new expressions), which were not very typical of the period. It examines the question of the autonomy of dance, the nature of the dance-like, but also the relationship between dance and sensuality, and between faith and artistic representation. It is also a result of the characteristics of the time, and especially of the political ideologies of Hungary at the time, that while mass sports, spectacular gymnastics and folk dance, which reinforced national consciousness, were all supported at the time, artistic movement needed to be accompanied by a pedagogical message that made it marketable, consumable and processable. The long-term goal was to integrate movement arts into the education system, but this required a precise and convincing programme.

Szentpál also describes artistic dance as an important tool for educating people, which

is the best pedagogical tool to balance self-control and the overcoming of inhibitions. From the point of view of mass education, there is no better means of developing willpower and unleashing latent potential than the pedagogy of the movement arts. The relationship between artistic dance and the movement arts should be thought of as the relationship between general music education and music. A certain elementary education is provided for everyone in school. Separate institutions (according to the music schools) would provide secondary education. And those who are called upon to do so would devote themselves to the pedagogy or artistic practice of movement art on the basis of a ‚college‘ qualification. In this way, the art of movement would be able to emerge from the soil of popular culture and find a resonant basis in a wide range of more or less competent enthusiasts.

(Szentpál, p. 30)

The second, methodological part is limited to a rather strict terminology and categorization, which is perhaps necessary, since it defines the law of rhythm (and distinguishes between musical rhythm and dance rhythm), the elements of plasticity, and what Szentpál calls the body technique, based on physical, music theoretical, anatomical rules. The methodology covers all aspects, but in a very sketchy way, at the level of mention. It was obviously more important than anything else to organise and to make the formalities, categories, groupings and connections in a methodological book clear and visible to anyone.

Szentpál believes that the practical aspect is the decisive factor in practical methodology, and for her the two most important such aspects are combination and enhancement.

She writes about the combination:

A wide variety of exercises and target aspects can be combined with each other, often also exercises that fall within the framework of different subjects (e.g. rhythmic and plastic arts, body technique and movement art, etc.). The pedagogue of movement art penetrates into the intricate field of dance and dance pedagogy only through continuous combinations.

(Szentpál, p.55)

After chapters on dance and movement technique that are often rigid, bounded and sometimes overly categorising, Szentpál shifts perspectives again, and tries to examine dance, the dancer’s work and his/her relationship to the world as a whole. She tries to illustrate the importance of intuition, the forms of empathy (abstract, dramatic and natural), the relationship between dance and the cosmos, and then she describes dance as a form of face-play and finally as an artistic style. Towards the end of the written part of the book, Szentpál returns to the style of writing we have become accustomed to in the first half of the book, using fiction in places, thinking in images, yet proceeding systematically, step by step.

This volume is much more than a methodological manual, it is also rebellious, innovative and, in places, extremely poetic and even philosophical.

While Szentpál and Rabinovszky remain on the subject of dance throughout, dissecting its shortcomings, its strengths, its role in society and culture, they provide an extraordinary chronology of 1928, both from a cultural and a social and political perspective. Almost all of Olga Szentpál’s volumes are still considered relevant literature on the art of dance, yet the quality of her descriptions of the artistry and the quality of her photographs make this one of the most extraordinary of them all. It raises several more questions, but it is also important to take into consideration the circumstances in which it was written and the context, the environment in which the dancer then worked and lived. The dancer, who was seeking for innovation and creativity.

The sections quoted from the book were translated by Eszter Petrány.

Szentpál, Olga, Rabinovszky M., dr., 1928. In: Tánc – A mozgásművészet könyve, Általános Nyomda, Könyv- és Lapkiadó R.-T. kiadása, Budapest

Dance – The Book of Art of Motion, Általános Nyomda, Könyv- és Lapkiadó R.-T. kiadása, Budapest

Olga Szentpál

Olga Szentpál (1895-1968) was a Hungarian pioneer of modern dance, choreographer, teacher and theoretician of dance. After her studies at the Hungarian Academy of Music she gained her diploma at Émile Jacques-Dalcroze’s (the founder of eurhythmics) school in Hellerau. She became involved in the modernist art scene through her husband Márius Rabinovszky (1895-1953; Hungarian art historian, art critic), and in modernist theatre as a teacher of Academy of Drama and Film in Budapest. She opened her own school in 1919 and established the Szentpál Dance Group in 1926.

from folk dance

through Szentpál

to us

Behind the richness of Hungarian folk dance notations

“Following the example of Bartók and Kodály in the field of folk music, the early concept of Hungarian folk dance research led by György Martin was that the corpus of Hungarian folk dances should get published as well. This concept was modified – due to the rapidly increasing amount of material collected for motion picture, the time and expenses – and, choosing different monographic forms, it was planned to publish only selected notation material in written form of the dances of the tradition which they considered worthy. In order to achieve this aim, they adopted a formal or musical analysis that was always published together with dance notation, and some of their summary works and regional, type or personality monographs included the notated dance notations as a substantial and extensive part of their dance materials.

Despite the fact that almost all major Hungarian folk dance researchers were familiar with dance writing, and also knew how to apply it on a notational level, they still employed a special dance notetaker for this task since the beginnings of the independent institutionalisation. This was necessary because of the specific preparations that each work needed and because of the huge amount of notation required. This task was belonging to Ágoston Lányi, who began his work at the Institute of Folk Art, and later continued his notation work at the Institute of Musicology of the Academy of Sciences. After his departure in 1986, his activities were taken over by the author of these lines in 1987.

Perhaps the result of a fortunate historical coincidence and the early wise decision of the Szentpál School (a workshop for the movement arts that operated between the two world wars) that from this large selection, Hungarian researchers became familiar with the Lábán kinetography, and applied it to record folk dances from the very beginning.” (Fügedi, 2014, p. 203, 204)

Guideline to our (or your own) creative work

Terminology

Rhythmicity: deals with the temporal relations of dance. (Szentpál, Mária, 1952, p. 29)

Plasticity: deals with the spatial aspects of dance and with the rules of its spatial flow. (Szentpál, M., 1952, p. 29)

Dynamics: deals with the degree and manner of force applied during dance. (Szentpál, M., 1952, p. 29)

Motif: The smallest unit of dance which (in itself) has an artistic, expressive power. (Szentpál, M., 1952, p. 29)

Gestures and movement principles

The following movement principles and gestures appear in The Book of Art of Motion in unique, expressive, emotionally loaded forms. The same principles are also used in Hungarian traditional dances, but in very different, specific ways. We compared the folk examples1 to the photos in Olga Szentpál’s book2 and with combining them, we tried to find new bodily and artistic solutions in our choreography.

- Rotations of the body – the role of the knees and shoulders, postures, indicators of directions;

- Different types of touches and holds – usage of fingers, hands, arms;

- Articulations of the feet (heels, soles, whole foot, inner- and outer side of the foot, toes, half-toe, half-heel) – using different parts of the feet, contacting the floor with the feet, turning these articulations into slides, jumps and turns;

- Partial and complete weight shifts – using different articulations of the feet for partial or full weight support.

The presence of NATURE

In Szentpál’s work

Olga Szentpál distinguishes between dance and dance art and labels artistic dance as the art of motion.

”Motion is the representation of life itself. Planets are in motion. Elements are moving, the wind, the rain, the wave, the fire – are all moving. Plants and animals are moving. The flower, the tree, the fish, the lizard, they can’t have a voice, but they all express their existence through motion. What’s more, the movements of mammals are able to express tempera as well: fear, anger, greed, disgust, joy and sadness.”

(Szentpál, O., 1928, p. 14)

In Hungarian Folk Dance

”Palm Sunday (czvéti), when nature begins to shed its winter clothes, is a typical Serbian holiday. The night before the feast, the girls gather around and sing a song about the resurrection of Lazarus (Lázár). The next morning, the girls gather outdoors before sunrise, sing, bathe in the river, walk the kolo dance. They are convinced that the wild beasts that populate the forests leave their lairs on this day and revel in music and dancing that cannot be heard or seen by ordinary mortals. The mysterious murmur of the forest is their talk, the gurgling of the streams is their chat, the smell of the grasses and flowers is their breath. Only those born in a cocoon (vilovnyak) can see and hear these enchanting and charming things. For the Serbs, this holiday is a celebration of the renewal of nature.” (Hadzsics 1891, Serbians living in the Southern Hungarian region)

1 https://neptanctudastar.abtk.hu/en/dances, last visited: 20.07.2024

2 See photographs above

3 In Knowledge Base of Traditional Dances, Research Institute for Musicology; https://neptanctudastar.abtk.hu/en/historicalsources?ItemId=%22Ttf.620%22, English translation by Eszter Petrány, last visited: 20.07.2024

Boglárka Heim

Boglárka Heim is a Hungarian dancer born in Miskolc, 1993. She started dancing at a young age, initially as a hobby that quickly developed into a lifelong interest and became her profession. In 2010, she began her contemporary dance education in Budapest. After her high school graduation at the Budapest contemporary Dance Academy, she furthered her studies in Austria at Anton Bruckner Private University focusing on contemporary dance and pedagogy.

Starting from the 2017/2018 season, she became a dancer at Nanine Linning Dance Company at Theater and Orchester Heidelberg. Following the time spent at the theatre, she continued working with Nanine Linning’s company until 2020, where she performed and toured with several pieces across Germany and Holland. For the following two years she was a member of Szeged Contemporary Dance Company.

Alongside her theatrical performances Boglárka Heim always had an interest in the film industry. In the past years she took part in several different projects, either as a performer or as a creator, including TV shows, commercials, series and films, such as in Stockholm Bloodbath, Ballerina and HALO. Her most recent work was in Dune: The prophecy, as movement coach and assistant choreographer.

Eszter Petrány

– dancer, dance teacher

*1991, Szentendre (Hungary); lives in Budapest

Eszter Petrány is a Hungarian contemporary dancer, started dancing at a young age with foundations in ballet, jazz and Hungarian folk bases. From 2012 she was studying contemporary dance and dance pedagogy at Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität in Linz, Austria, completing her bachelor´s and master´s studies in 2018. During those years Petrány started to work as a freelancer dancer with Cie. Of(f)Verticality and as a dancer at Landestheater Linz.

As a dance artist she explores topics that include different perspectives on the functions and roles of musicality, verbality and poetic qualities in dance, which were strongly reflected through her solo of The Diary of Anne Frank. In 2018, she joined PUC Collective with her dance role in Bauhaus Tanz. In 2022, she danced a solo part in Das Gesicht im Spiegel with Neue Oper Wien.

Petrány is currently a PhD student at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design. Her research is focused on improving the perception of dance archiving methods, scoring systems and on discovering their potential compatibilities. In the past years, she has also begun collaborating with filmmakers and photographers. Her most recent work was in Dune: Prophecy, where she appeared as a dancer and in the role of a ‘small part actor’.

Marcell Török

– director, media design artist

*1990, Zalaegerszeg (Hungary); lives in Budapest

Marcell Török is a Hungarian film director and media designer. He started his bachelor studies at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design. In 2015 he continued his studies at the University of Theatre and Film Arts, Budapest as a B.A. student of film directing. In 2019 Török started his master studies and he received his degree at Filmakademie Wien. Marcel Török works at Katona József Theatre as a media designer and as the leader of the video library. In 2022 he directed Találkozás, which had a special format between a theatre piece and a film, since it was created for streaming platforms. In 2023 Találkozás (by P. Nádas and L. Vidovszky) won a prize for the most original format and artistic language, as well it was awarded by the special prize of the jury. His 2023 short film Third Day (Harmadnap) was also recently awarded at Friss Hús Film Festival. Török is currently working on his first feature film, which is a mockumentary and is expected in 2024.

Bibliography

Fügedi, János, 2016. In: Basics of Laban Kinetography for Traditional Dancers, © Institute for Musicology, Research Centre for the Humanities, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest

Fügedi, János and Fuchs, Lívia (2016) „Doctrines and Laban Kinetography in a Hungarian Modern Dance School in the 1930s,“ Journal of Movement Arts Literacy Archive (2013-2019): Vol. 3: No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/jmal/vol3/iss1/3

https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=jmal, last visited: 05.06.2024

Fügedi, János (2014) Táncírástár és Motívumtár. ZENETUDOMÁNYI DOLGOZATOK. pp. 203-208. ISSN 0139-0732

Szentpál, Mária,1952. In: Hogyan olvassuk a Táncleírásokat, Művelt Nép Könyvkiadó, Sopron

Szentpál, Mária, 1964. In: Táncjelírás: Laban-kinetográfia, 1 – 4. kötet, Népművelési Intézet, Budapest

Szentpál, Mária, 1964. In: A mozdulatelemzés alapfogalmai: kézikönyv a táncleírások olvasásához / Sz. Szentpál Mária; [a rajzokat Benkő András kész.] ; [közread. a] Népművelési Intézet, Budapest

Szentpál, Olga, Rabinovszky M., dr., 1928. In: Tánc – A mozgásművészet könyve, Általános Nyomda, Könyv- és Lapkiadó R.-T. kiadása, Budapest

Links

Knowledge Base of Traditional Dances, Research Institute for Musicology

https://neptanctudastar.abtk.hu/en

last visited: 20.07.2024

Orchestics Foundation

https://moha.mozdulatmuveszet.hu/?page_id=477

last visited: 20.07.2024